MAPLE

Introduction

I wrote this piece for my friends who asked about my experience staying at a monastery in 2020, the Monastic Academy for the Preservation of Life on Earth (MAPLE). A lot was left out because it would require too much context, such as many of the day-to-day questions I had, the concepts I learned, some beautiful moments of clarity, and my despair as I considered my own mortality and the potential collapse of civilization. I hope your takeaway from this is not that monasteries are perfect, but that many, especially MAPLE, are helping people do amazing things.

How did I get here?

I spent 5 weeks staying at a monastery in 2020. That January, I was thinking it would be a long time before I did another meditation retreat, having just dipped my toes in at a two day retreat the previous year. However, the pandemic messed with my head in many ways and I found myself more amenable to trying another retreat.

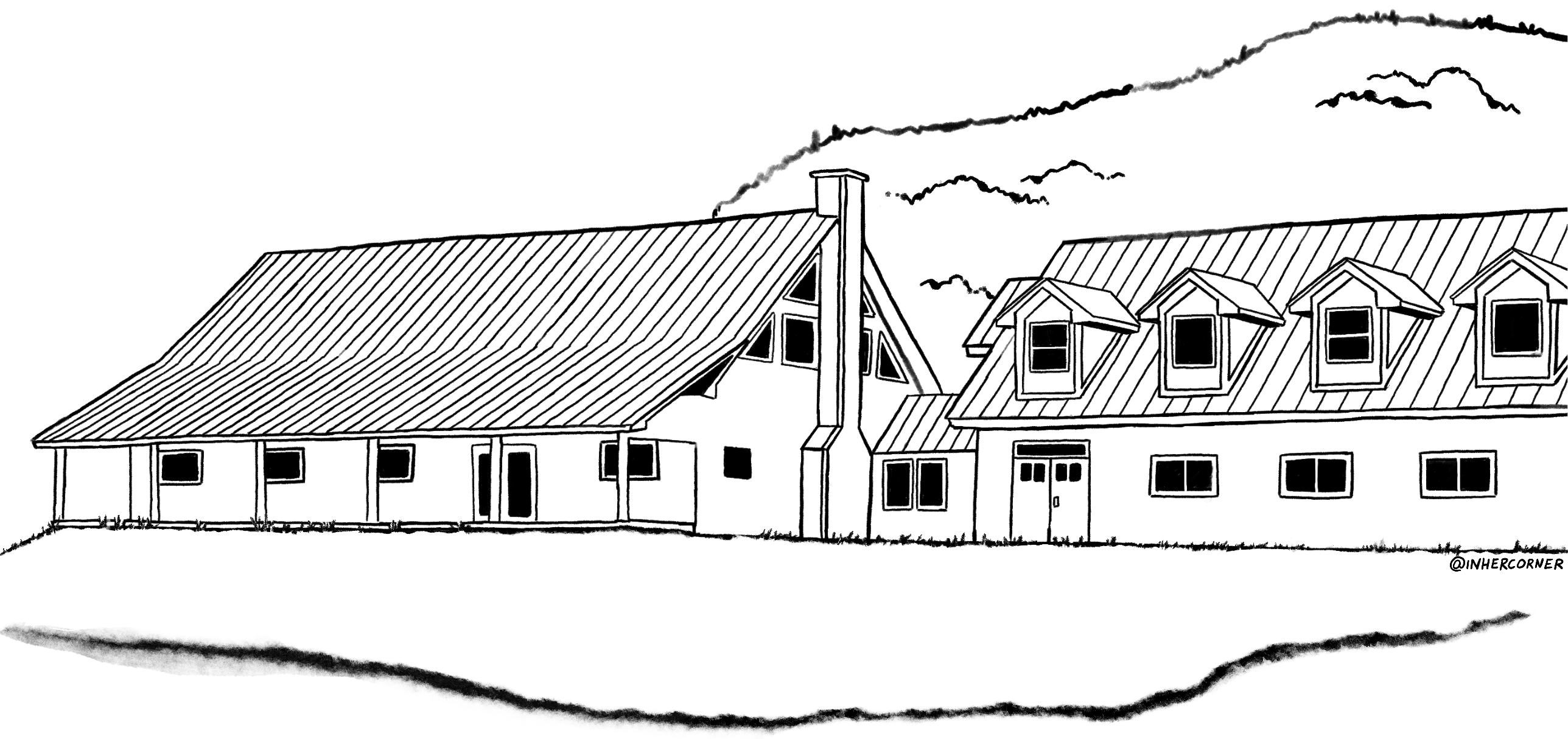

It began when my close friend Tasshin emerged from his multi-month solo retreat in a cabin. He had been involved with MAPLE since 2014. Following his cabin retreat in 2020, he invited me to come visit the monastery, a beautiful barn-house situated in rural Vermont. I don't know the full story of its founding, but I've been told its teachers are largely influenced by Zen Buddhism, with some American characteristics.

When Tasshin first suggested I visit, I was not very interested; however, the invitation stayed in my thoughts over the following weeks. Some days I feel a bit more lucid and bold than on others and on one such day, I decided to look at the registration form for one of MAPLE's week-long retreats. In my head, a strange sequence of thoughts occurred: “Wow, this is absolutely not something I would ever go to. I should definitely go. It would be so unlike me!” Thoughts like this are the ones that have shaped my life in the past.

If I went, I would need to drive, because it seemed risky to share transportation with others. Unfortunately, I had misplaced my driver's license and the California DMV had failed to send me a replacement in the mail three times since the beginning of the pandemic. I was also feeling more cost-conscious than normal, as I was saving up to quit my job and possibly move to Taiwan later that year—something that made the retreat seem expensive.

But then something miraculous happened. I put on my face mask and went down my apartment stairs to check my mailbox. Not only had a replacement driver's license come that day, but I also received a stimulus check from the government for roughly the price of the retreat. Before I went to bed that night, I bought a ticket for the retreat and wished my future self the best.

The Retreat

I went to the retreat full of expectations. I had experienced pain when sitting to meditate in the past and anticipated to feel even worse pain sitting for longer periods at the monastery. Additionally, Tasshin had told me that the head teacher, Soryu Forall, could be quite intense. Hundreds of hours spent talking with others about rationality had led me to develop a reluctance to engage with people and institutions that weren't explicitly evidence-based. But my communication with the people living at the monastery was very reassuring and I trust Tasshin considerably.

I and five other visitors joined the monastery for the week of the retreat. Most of us had a cozy room to ourselves, with a great view of the surrounding nature. The members of the community were very friendly and accommodating.

Each day of the retreat had roughly the same schedule, yet each morning when I awoke, the previous day's events led me to ask deeper and deeper questions about what kind of person I was and how everything works.

- 4:40am: Morning meditation and chanting. A teacher provides 1:1 guidance (interview) to as many people as they can in a separate room.

- 6:35am: Exercise.

- 7:35am: Breakfast. Simple vegan food, with occasional vegetarian exceptions. We chant before and after each meal.

- 9:00am: Listen to a talk by a teacher, often accompanied by meditation and exercises.

- 11:30am: Chores to maintain the monastery.

- 1:05pm: Lunch. Similar to breakfast.

- 2:30pm: Self-practice period / free period.

- 4:30pm: Listen to a talk by a teacher, often accompanied by meditation and exercises.

- 7:00pm: Evening meditation and chanting.

- 9:30pm: Silence until after breakfast.

Waking up at 4:20am each morning definitely made me tired. At first, I was tired for several hours after waking. However, after a few days, the fatigue only lasted about thirty minutes. The chanting in the morning was what really woke me up each day. I only knew that I was getting less sleep when I sat down to relax. Fortunately, there aren't many idle moments at a monastery.

Before I came to MAPLE, I had never chanted with a group. I went to a Jewish temple on Saturday mornings many times as a child, but the prayers we sang at the temple were long and varied; the chants at MAPLE are generally shorter and more repetitive.

Excerpt of our chanting The Heart Sutra. It starts out quiet, slowly building in volume, speed, and pitch until reaching a climax, then returning back to the beginning.

I was encouraged to give myself completely to the chant and not hold anything back. If I had the capacity to think about what I was doing, then I wasn't putting everything towards it. This idea was pervasive throughout the monastery, from doing chores to cooking food to sleeping: Make an effort. Every moment is an opportunity to practice.

I assumed I wouldn't like Soryu, the head teacher, because the Buddhist tradition seemed at odds with my enthusiasm for rationality and non-religion. Anyone who ventured to believe without empirical evidence, I thought, must be impossible to have a sensible conversation with. And in some capacity that's true, if we only look through the lens of modern culture. I came in thinking that Buddhism was not evidence-based and its teachers made it up as they went along, but talking with people at MAPLE made me realize that Buddhism is all about learning through yours and others' subjective experience. It is incredibly dependent on using evidence, just evidence that is hard to empirically reproduce. It also boasts communicating and improving on ideas over 1000s of years, something that frameworks like the scientific method have yet to achieve.

And I was surprised to find myself really drawn to Soryu. He is extremely intelligent, well-read, unassuming, funny, and persuasive. I was floored by the talk he gave on the first night. He spoke about making excuses and the stories we tell ourselves to avoid feeling our feelings and thinking about our complicity in the destruction of life on earth (also check out Soryu's Embodying the solution.

I hesitate to try communicating more of Soryu's ideas here because I feel as if I've only scratched the surface of understanding his teachings and taking them out of context lends well to straw-man arguments. Nevertheless, I want to share some of his ideas that I found striking and easier to understand: Modern cultures use science to understand what is and employ Humanist philosophies (e.g. Liberal Humanism, Communism, National Socialism) to decide what ought to be. Instead of each of us trying to love all beings in order to go to Heaven (or some equivalent), we pursue a God-like experience here on Earth that leads us to ignore ethics and use science to destroy nature and other living beings. However, human wants and feelings are not the most important thing in the universe and the monastery is a place people go to learn how to accept being perfectly normal.

The talks by Soryu and other members of the community were inspiring, but learning some of the mindful techniques was also quite useful. Each of the techniques corresponded with one or more parts of the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism. Some examples are:

- Circling: An intersubjective meditation where each person in a small or large circle tries to stay with exactly how they're feeling at the present moment and what they're feeling about others.

- Bio-emotive (similar to Focusing): A technique to help one feel emotions that are present in one's body but are impeding mindfulness practice.

It's hard to describe the environment at MAPLE, where not only do people listen generously, but they try to deeply listen to each other as part of their practice. Of course, the people at the monastery weren't perfect: sometimes they arrived late to events, acted selfishly, or made mistakes. The others didn't overlook them though; in fact, giving helpful, direct, honest feedback (Right Speech) was common and encouraged. I felt heard when people listened to me and I felt cared for when people gave me feedback. I knew that, although I occasionally felt defensive after receiving feedback, the person giving me the feedback was kindly sharing a lesson they had learned in the past.

Having this kind of trust in the members of my community let me stop worrying about whether others were doing their fair share or taking advantage of me. Many hugs were exchanged on a daily basis, which is something I rarely took part in, even before the pandemic. The monastery was bursting with love.

The Month

Leaving the monastery to go back to my New York apartment was very jarring. I resumed studying Chinese and quit my job the next month. I had dipped my foot in this time and enjoyed the temperature, having answered some questions and spawned a multitude more. Compared with being alone in my apartment with no one to talk to besides my roommate and a computer screen, the monastery was a beacon of joy.

I wanted to go back and stay a little longer; however, a few obstacles stood out in my mind: I didn't want my Chinese practice to attenuate, I hated getting up early, and sitting for meditation practice was still quite painful. I promised myself that I would work on sitting better if I went back to the monastery and, as for Chinese practice, I opted to go back to MAPLE as a coworker. At MAPLE, a coworker is generally someone who stays at MAPLE and does their personal/professional work, while still engaging in the morning and evening schedule (and whatever other events they want to go to). This felt like a convenient way to get a longer exposure to monastic life while still maintaining my obligations and interests outside of the monastery.

I arranged to stay for four weeks starting in October. My first week was another retreat, much like the one I went to earlier in the year, but the rest of my time there I focused on learning Chinese (along with my other strange interests).

It took some time getting used to my place at MAPLE, as I was one of three coworkers and the only one working on something unrelated to mindfulness. Many of the people I had met during the retreat earlier in the year had left because they had been apprentices, another role at MAPLE that lasts about two months, so there was a lot of energy in the new cohort of apprentices that coincidentally arrived when I did.

One of the best outcomes from my four weeks was I figured out how to sit well and eliminate almost all of my pain. Getting a wider base by putting both of my knees and forelegs on the ground helped reduce the pain, but the biggest improvement came when I figured out this technique:

The Cannon Technique: Think of the pain you feel on your back, in your shoulders, and your neck as knotted balls of energy. You are a fortress. At the site of your pain, a small cannon emerges from your body and shoots the energy away, moving the sensation somewhere else.

The Buddhist tradition seems quite psychosomatic, so it's possible this technique will only work for me, as it's the result of many hours of iterating on a breath technique Tasshin taught me.

The retreat at the beginning of my four week stay seemed to pass very slowly, but then the weeks came quickly and it was already time for me to go. On the last night, as we were chanting “Om Mani Padme Hum”, I realized how much I cared for the people at the monastery and I cried profusely, more than I had in years. By the end of the chant, I was, as they say, a slobbering mess. I recommend MAPLE's coworking program of any length to anyone who feels like they'd like to visit the monastery but are not quite ready to give up their job.

After

I'm still sorting through my thoughts on my visits to MAPLE. I never overcame my distaste for the early wake-up time and it remains one of my reservations about going back to the monastery for a longer stay. I'm more interested in Buddhism now than I was before, although my mindfulness practice has been infrequent since I left the monastery.

While at the monastery, I thought a lot about my death. Barring some breakthrough in biological science, I will die relatively soon (<100 years). This is pretty hard to accept, but I think about it more now and I believe this is an important line of thinking.

I also now place a higher priority on working through my feelings, although I notice that some weeks I feel a little numb without the support of a community. I feel like I can't go back to the life I had before the monastery, but also the life in the broader world doesn't allow me to live with the same integrity I had at the monastery. Yet I don't feel ready to commit to more time at the monastery, so I feel caught between. Conversations with a few people who have also left the monastery suggests similar sentiments. Perhaps this is the life in which I awaken or perhaps it's an opportunity to learn something for the next go. I don't feel sure of anything and that feels like progress.